Fall has arrived, the season that calls us to look to the trees. Yesterday I went on a tree walk led by local herbalist (and former arborist) Alex Klein, our area’s “tree walker.” We meandered through a small stretch of the Jamaica Pond shore over the course of two hours. It’s not really a tree walk because there’s little walking needed when there are so many trees to say so much about. As always, it was a wonderful time, and it didn’t hurt that the weather was perfect. This is the part of the year where it seems like every week I say “This is the last perfect day of weather before winter!”

I’ve been reading a lovely book called A Year in the Maine Woods by Bernd Heinrich, a biologist specializing in birds and insects, professor emeritus at Vermont University, and decorated masters ultramarathoner. Today, I was reading the October 1st entry, titled “Foliage” and I wanted to share some of it. Here goes:

“Mostly what’s on my mind right now are the fall colors. I go around gaping, as if I have never seen anything like it before. Perhaps I haven’t, I’m never quite sure. I could see this display every year and not grow tired of it, like seeing the flight of geese, or hearing the bird songs in spring. I remember, and that might reduce the amazement. But I don’t remember the edge—the vividness of the spectacle…

The maples are the primary show— specifically, the two forest canopy species, sugar (Acer saccharum) and red maple (Acer rubrum).

Of the 100 sugar maple trees that I examined, four were “orange,” four were brownish, and all the rest were golden yellow. The golden crown of a sugar maple tinged with orange can startle you with its lumines. cence. But it doesn’t hold a candle to the red maples, whose color varies from pale lemon yellow to scarlet red to deep purple, with every imaginable gradation in between. Of the 128 red maple trees that I surveyed around my clearing, I rated 33 as “purple,” 21 as “deep pink,” 52 as “red to orange,” and 22 as “clear yellow.” There seemed to be no rhyme or reason to the colors. Even the first set of two leaves that tiny seedlings sprout are brilliantly colored, just like those of giant trees. I could determine no correlation with age nor location, at least in the red maples: a purple tree could be right next to a yellow one. In contrast, the few mountain maples whose gold leaves tended toward orange grew in sunny exposed spots, and the few purple- or copper-tinged ash were also the ones more exposed to direct sunshine.

Although from a distance the red maples each looked distinct and uniform in color, that uniformity disappeared on close inspection. The crowns and tips of branches turned color first, so that if you watched a tree in time-lapse, a gradual blush would envelop the tree from the extremities in.

Looking still closer at individual red maple leaves, you saw even more variety. On some trees, the individual leaves were uniformly hued like the whole tree. On others, however, it looked like a mad spray-painter had been busy: yellow leaves might be marked with bold red blotches, or finely speckled in red or pink.

The leaves of the red maple drop at the height of their color, and all the while that the forest is ablaze in color from the underbrush up through the tips of the crowns, the ground also is aflame as the magic settles onto the wilting ferns and last year’s decaying brown leaves. I want to pick up every leaf, for each one seems brilliant and unique. I know that the colors are even more precious because they are ephemeral—in a few days they all fade to a uniform brown. To remind myself of what they look like, because my memory will fade almost as quickly as the leaves themselves, I picked up those that struck my fancy as I walked up the half-mile path from my jog down on the highway. From that short walk I compiled the following list, in testimony to the astounding variety of color, to be browsed at random in the same fashion as one might enjoy the leaves themselves:

- yellow with small purple blotches

- green center with shining red margins

- light lemon yellow

- yellow with dot-sized red speckles

- uniform bright vermilion red uniform pink

- yellow with washes of red and orange

- greenish yellow with one bright red corner

- orange with large red blotches

- bright uniform luminescent red

- pale yellow with green veins

- green with red spots

- yellow with red washes and mottling along veins

- greenish yellow with diffuse red washes

- red with purple veins

- yellow with purple edges

- gold evenly speckled with red

- yellow with green mottling

- red with yellow veins

- pale yellow (almost white)

- gold with three bright red dots

- purple with green blotches

- bright vermilion red with yellow veins

- uniform peach

- uniform orange

- peach grading into pinks and yellow

- yellow with dots that look like blood

It seemed odd that color should vary radically even within a given leaf. Why should two leaves on the same tree, with genetically uniform cells, have totally different colors? Was I looking at a progression of colors that all leaves underwent, uniformly-say, from green to yellow to spotted to uniform red to purple? To find out, I marked 20 individual leaves with tags attached by dental floss and rechecked them when color was complete and they started to fall off. I learned that a leaf that started to turn yellow continued until it was fully yellow, then dropped off. The same process occurred with a red or purple one. Any spots showed themselves early, and they did not enlarge, contract, appear anew, or disappear. It was as if each green leaf destined to have spots had a spot pattern program within it that predetermined one specific pattern. On the other hand, the overall pattern or base color cannot be immutable from the time the leaf first forms, because when a branch is partially broken or damaged, the leaves on the broken part turn a different color than the rest. The later the break, the less the difference in color. In the same way, leaves that are picked and allowed to dry are arrested in their color development-they dry green, green-yellow, green-red, or whatever color they had when they were picked.

In the previous year when I had thinned out the red maples from my sugar maple grove, I had already been impressed with the various autumn colors of the leaves from the red maple sprouts that had regrown by that fall. I had photographed them on individually identified trees, hoping to compare the colors with next (this) year’s. Of the 15 small trees I revisited, all had similar colors as before: previously purple trees tended to be purple again, yellows again yellow, and so forth. There was some uniformity to the fall colors after all.”

I love this passage for several reasons. One of them is that it shows how anyone can be a naturalist or scientist. Here is a professional biologist, decades into his career, asking a really very understandable question about trees: at what point do maple leaves, which all start out green, become different colors, or do they all follow the same sequence? It is simply answered: he just tags a bunch of leaves with dental floss and then checks them over and over again. He discovers a piece of truth through simple, planned observation. In contrast, plugging this question into some AI chat bot would be a worthless, forgettable experience with no backbone of truth. Most likely, the answer would be rubbish, a bunch of regurgitated facts that don’t answer the question, but it’s not even worth the electricity to me to make an example out of it.

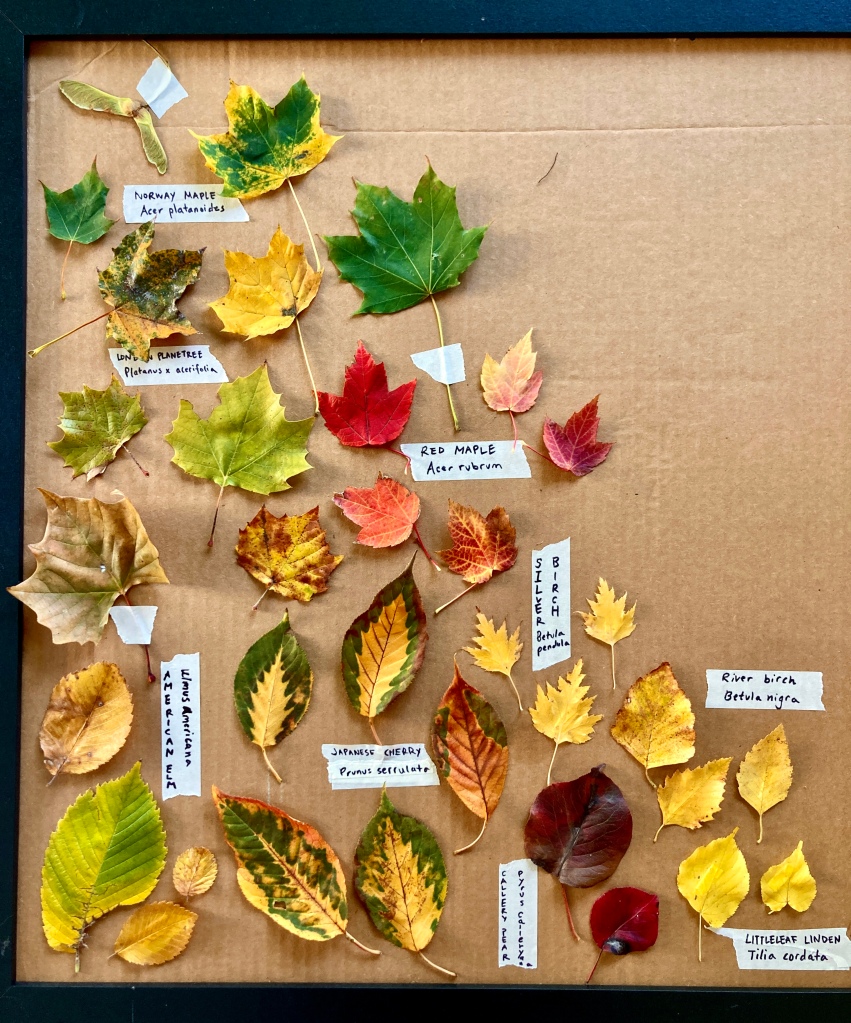

After reading this passage and deciding to share it, I went for a short walk around my block and collected fallen leaves. Like Heinrich, I simply grabbed whatever leaves struck my fancy. I also looked for what tree they had fallen from to help identify their species. I began observing which trees had and hadn’t started to drop their leaves yet: a small fraction of most trees’ leaves had started dropping, which the exception of mulberry and cherry plum, for which I couldn’t quickly find any fallen leaves.

I arranged my harvest on the cardboard back of a picture frame, labeled the species with their common and scientific names, and hung them on the living room wall. Lots of space was left for future leaves, and I look forward to completing this collection as the season progresses.

I have a lot of half written blog posts languishing in my drafts, because I have things to share but I’m also very busy with starting a new business/career/life. The one thing I have published elsewhere recently is a blog post about leading my first cob build and teaching my first natural building workshop in New York this September. Feel free to check it out if that interests you.

Until next time, enjoy the leaves.

Discover more from evoiding

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.