Storytime!

As some of you know, I recently (mid February) quit my job in battery engineering (which I had worked since I graduated college, for 1.75 years) to do natural building related work as both a profession and passion. As I keep on saying to everybody, I’ll be sharing more about this in writing soon. But I’ve been so busy doing the thing and figuring out the thing that I can hardly find the capacity to write about the thing!

Anyhow, this post is about one more step on that path: my journey to Moab, Utah for a 2-month internship at Community Rebuilds, an sustainability-minded affordable housing nonprofit. Earlier this year, I applied to and was accepted to their “Builder B.E.E.S.” (a backronym for Building Energy Efficient Shelter) internship/volunteer program. Now I had to get there.

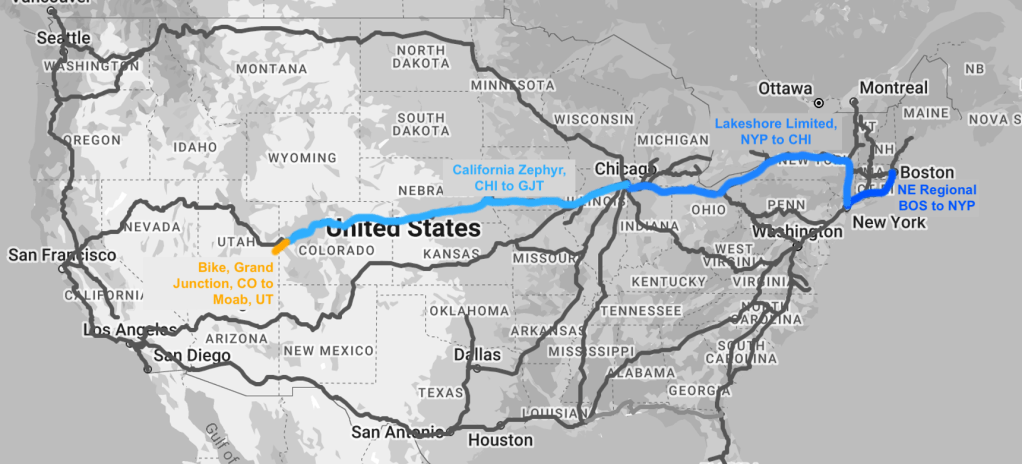

I do not fly at all (no flights since 2021) and avoid being in cars (averaging perhaps 4 hours per year for the past couple years), and travel by train and bike instead. Having two multi-day bike trips under my belt (MA, TN), I was comfortable with the idea of getting myself to Moab. The plan was to ride Amtrak, over the course of several days, with several stops, from Boston to the nearest bike-accessible station, in Grand Junction, CO, and then bike the remaining ~115 miles over 1-2 days.

Amtrak Nerd Details (click dropdown to read)

If you’re knowledgable about Amtrak, you might be wondering why I went down from BOS to NYP instead of straight across on the Lakeshore Limited starting from Boston. The reason is because you cannot take a bike on the branch of the Lakeshore Limited between Boston and Albany. Either that branch of the LSL doesn’t have a baggage car to put the bike in, or, the baggage car’s contents cannot be transferred when the two LSL branches join in Albany and continue to Chicago. If you know more, do tell. So my bike and I had to take a slightly longer route, taking the NE Regional to NYP first, where I can bring a bike into the train car itself, and then get on that branch of the LSL, which you can check a bike in the baggage car and get it at the final destination, Chicago.

The total time on train was about 60 hours, so I scheduled the three segments with a day in between each, which served as time to stretch my legs, eat some fresh food, sleep completely horizontally, and catch up with friends. This was also a safeguard against delays: the last thing I wanted was for a delay on one segment to make me miss the next, or wind up late for my first day at work. My stops were in New York and Chicago, which made it easy to find places to crash and people to see. It was wonderful to catch up with friends, and I was lucky to enjoy great weather in both cities.

I was less lucky that first day of my departure from Boston. It had been raining since the wee hours of the morning, and I didn’t have proper rain gear, so I got pretty wet on the 20-minute ride to the station. Foreshadowing.

The first two train rides were fairly uneventful: as expected, it took about 4 hours from Boston to New York, and 20 hours from New York to Chicago. I slept poorly between New York and Chicago, unaccustomed to sleeping in a train seat.

It had been many years since I was last in Chicago, so it was basically a new city to me. I was pleasantly surprised by its ease of bikability. Compared to Boston and New York, the streets were very wide and empty, and there were often bike lanes. It was warm, sunny, and windy, too, as the reputation goes.

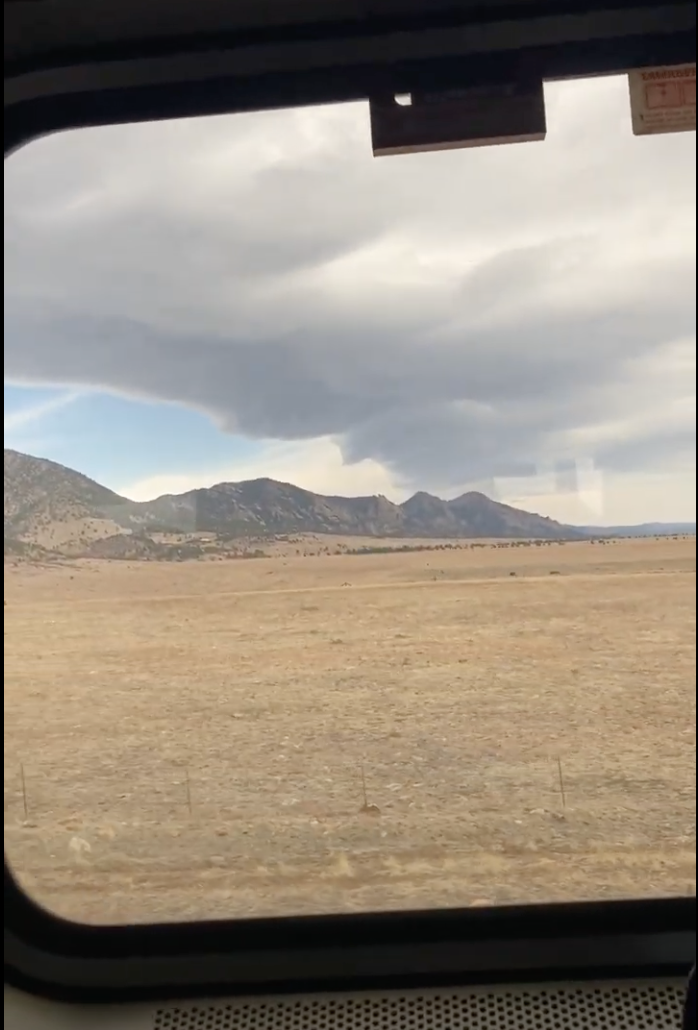

The ride to Colorado on the California Zephyr was the longest, projected to be about 27 hours, but the most scenic. I departed Chicago around 5 p.m. and woke up to a Southwestern landscape. The farther we went, the more scenic it got.

I slept, read, and did some more mending on my panniers.

The story of my panniers

In a very nice stroke of luck, I snagged two waterproof Ortlieb panniers from my local free stuff Facebook group last fall, right before my trip to TN. Their owner, a bike tourist himself, was giving them away because they had a manufacturing defect: the welded seams were coming apart. Ortlieb, per their lifetime warrantee, sent him new ones for free, so he was jettisoning the old pair. I’d sewn up the open seams before my TN trip with polyester thread, but new gaps had opened since, so I had more sewing to do before this ride. It makes me happy that I got them for free and gave them a new life instead of sending more material to the landfill and stimulating more new production by buying new. These panniers are almost entirely plastic (poly or nylon fabric, plastic waterproofing coating, plastic mounting hardware, which the exception of a little bit of metal in the hardware) which I am very conscious of the production and disposal of.

The next afternoon on the California Zephyr, we hit a series of unfortunate events. A rock on the tracks set us back about 2 hours to get it removed and the track inspected. Later, a car on the tracks cost us another 90 minutes to get it removed. Finally, the first two delays pushed us prematurely past the employees’ 12-hour shift limit, so we waited another 90 minutes or so for a replacement crew to drive out. In total it was about six hours late, so I arrived in Grand Junction well after dark.

I stayed with a very wonderful retired couple that I’d found weeks prior via Warmshowers, a website for bike tourists to find and offer couch-surfing. The next morning, I had breakfast with them and left soon after sunrise. It was raining, unfortunately, but I had places to be. I’d left myself two days to bike to Moab, so there was no time to waste to ensure a timely arrival for the internship.

It rained lightly for the first few hours. It was about 40 F: “Could be much worse, this is handleable,” I thought. A few hours in, though, my pants were totally soaked on the upper sides, my windbreaker was soaked, and my sweater was on its way. I was glad I’d brought my Bar Mitts, which kept my hands fairly dry, if I remembered to occasionally shake the water off my sleeves so it wouldn’t run down to my hands.

I made a final water stop in Loma, at a gas station. There wouldn’t be any reliable water source for the next 100 miles. Under the roof overhang, I made and ate a strawberry jam sandwich (my entire fueling plan: a jam sandwich every hour). “You’re tougher than me,” a gas station customer said as he walked past. I probably looked pretty sorry, a sodden lump with a helmet. But I was feeling pretty good, still warm and full of energy.

As I continued on U.S. Route 6, an old highway which was fairly empty now that a bigger interstate highway had been built next to it, cars became fewer and fewer. The landscape was fairly unremarkable: just flat desert, with mountains in the distance. The rain finally stopped around midday, although the clouds continued to obscure the sun. An hour or two later, I was mostly dry again! My spirits were high and so was the cell reception. I texted my mom that it was all going well.

Of course, it then began to rain again. Now, it was coming down in sharp little frozen specks that stung my face. I pedaled on. My route took me off the highway, onto a Bureau of Land Management road that headed towards the hills. This is where I diverged from the wise path.

The rain persisted and got heavier and I started to get bonafide soaked to the skin. “This has gotta be more than 0.15 inches,” I thought about the weather report with irritation. Cell reception dropped out, which I didn’t really need, per se, since I had my route downloaded, but reception is always nice to have. As the road wound through hills covered in orangey boulders, I got colder and wetter. When was the rain going to stop? I started eyeing the boulder fields at my left, wondering if I could find shelter under one. At one particular moment, I realized that this all was getting concerning, and decided to stop. It was time to make shelter.

Pelted by rain, I dragged my bike and its luggage (perhaps 70 lb total) up the side of the road. I hiked to the top of the small, steep, hill and found it to be flat enough to camp on. I hiked back down, pulled off my panniers and camping gear, making sure to keep my sleeping bag wrapped in my Tyvek tent footprint, and hauled it up. Then I stowed my bike behind a big rock, near the road. Then it was back up the hill again, my boots getting thoroughly soaked and coated in thick mud, to set up my tent. Finally, I shucked off my wet clothes and shoes outside, and crawled into the tent where I quickly changed into a dry set of clothes, inflated my sleeping pad, and unrolled my sleeping bag to keep warm. Snuggled inside, head poking the sagging top of my hastily staked tent, slowly but surely warming up, I reflected on my stupidity.

I wasn’t sure if it was raining more than projected, but regardless, I should have been prepared for this much rain. Proper, full coverage rain gear would be a first step. Deeper prevention would be planning my travel so that it left more days to complete the bike, leaving time to wait out a rain day. I wasn’t stewing too much about should-haves, though. I was also thinking about what to do next.

I had two options: call it for the day after only 6 hours of biking, spend the night on this hill, or wait for the rain to stop and continue. Either way, I only had one thing to do at the moment: wait. And eat a jam sandwich.

About an hour later, the rain finally stopped. The clouds cleared a little. I poked my head out. It was the sunniest it had been all day. I began to have the impulse to get back on the road. I had too much energy to want to hunker down for the rest of the day, and if I could, why not get more miles done to lighten the load tomorrow?

So I climbed out of my tent, put on my soggy boots, and de-bivouacked. One moves rapidly in the cold. I blasted some music from my phone to hype myself up as I hauled my stuff back down the hill and repacked the bike. Then I was rolling again.

I had perhaps one hour of cheery riding, under the warming sun, before my mistakes made themselves evident again. I passed a sign for the Kokopelli Trail, a well-known multi-day bikepacking/mountain-biking route, also between Grand Junction and Moab. I had chosen not to take the Kokopelli because it would several days longer than the road route, making bringing all my water virtually impossible, and mountain biking was foreign to me. I went a mile the other way before checking my route map. Whoops. I was indeed charted to go on this part of the Kokopelli Trail.

I turned back, and with a little trepidation, entered the trail, a two track dirt path with rocks aplenty. Less than half a mile in, I started to hit mud. Multiple inches of slippery, clayey mud that I could not bike through, forcing me to walk and push. Even walking was difficult, each step sliding backwards. Furthermore, the thick mud, containing stones, was tracked up into my fenders, where it completely filled the gap between my wheel and fender at the back ends and jammed it up. It was slow and difficult going, alternating between muddy spots and drier ones. Eventually, I realized that at a pace of 1 mile per hour, this was not a feasible route. With sunset approaching in about an hour, I decided to stop and camp for the night.

I set up my tent, wishfully hung up some clothes to dry in the hour of remaining sunlight, ate some food, and removed my wheels to scoop handfuls of mud out of my fenders before it could dry or freeze overnight.

In my tent, I plotted. Hopefully the trail would drain, dry, or freeze overnight, making it firm enough to bike out of. I also inspected my route on Komoot, the navigation app I use, more closely. Indeed, it had me going on Kokopelli for about 8 miles before meeting paved road. I decided, if the trail conditions were truly fantastic tomorrow morning, I would continue on this course. If they were questionable at all, I’d backtrack and take the highway for an all-paved route to Moab.

The sun set. I bundled up in three layers inside my sleeping bag. Without the constant motion of the day to occupy my mind, it was just me and my thoughts. I was maybe the most alone I’d ever been. There were no other humans, except those passing obliviously in the rare Amtrak passenger train, for miles. There was no cell signal, so no virtual interactions to be substituted. Despite my efforts to think rationally (“Nothing’s going to happen, nothing’s going to happen,”) I could feel my heart pounding and nerves firing at every rustle of my tent in the breeze. To soothe myself, I read for a while on my phone (one of the few books that I had locally downloaded, it turns out, was a childhood favorite, Airman by Eoin Colfer). Thankfully, I soon fell asleep.

When I woke in the middle of the night, I crawled out of my cozy nest to a sky full of stars, which I could see even without my glasses on. I clambered back to get my glasses and beheld the starriest night I’d seen in months. It was dead silent. The air was still.

The next morning, I woke up with the sun. I’d slept well, for over eight hours.

Somewhat reluctantly, I peeled myself out of my sleeping bag and got out into the chilly, overcast morning. I jogged over to the trail. Yes! It was firm: the mud had frozen, which boded well for getting out of there promptly.

I hustled to pack up my stuff, both to keep warm and to gain momentum for the day ahead. The dance reversed: my things went back in the panniers, one pannier for wet things and one pannier for dry things, my tent rolled up, panniers hooked back onto the rack, then tent and sleeping bag bungeed on top. I’d lost one glove and the other had gotten wet with frost, so I put socks on my hands. Soon, I was rolling down the path, back the direction I’d come yesterday.

With the mud frozen, it took me merely 20 minutes to backtrack what had taken maybe 90 minutes yesterday. Another hour or two took me back to the highway I never should have left. Cars whizzed by and cell signal was back at full strength.

Another hour or two of blissfully uneventful highway shoulder biking proceeded, punctuated only by my perusal of the scattered contents of a smashed bin that had clearly fallen out or off of someone’s car at some point in the history. Although I was pretty good on food and water, I selected a bottle of unopened margarita mixer (water and sugar, score! Tasted funky though.) and half empty bag of granola (crunchy with a hint of road) for backup.

Eventually I turned off U.S. Route 6 onto a much smaller and quieter highway, Utah State Route 128. This took me further into the shrubby desert terrain that I’d been in, intersected by the occasional fence, once or still used to enclose cattle.

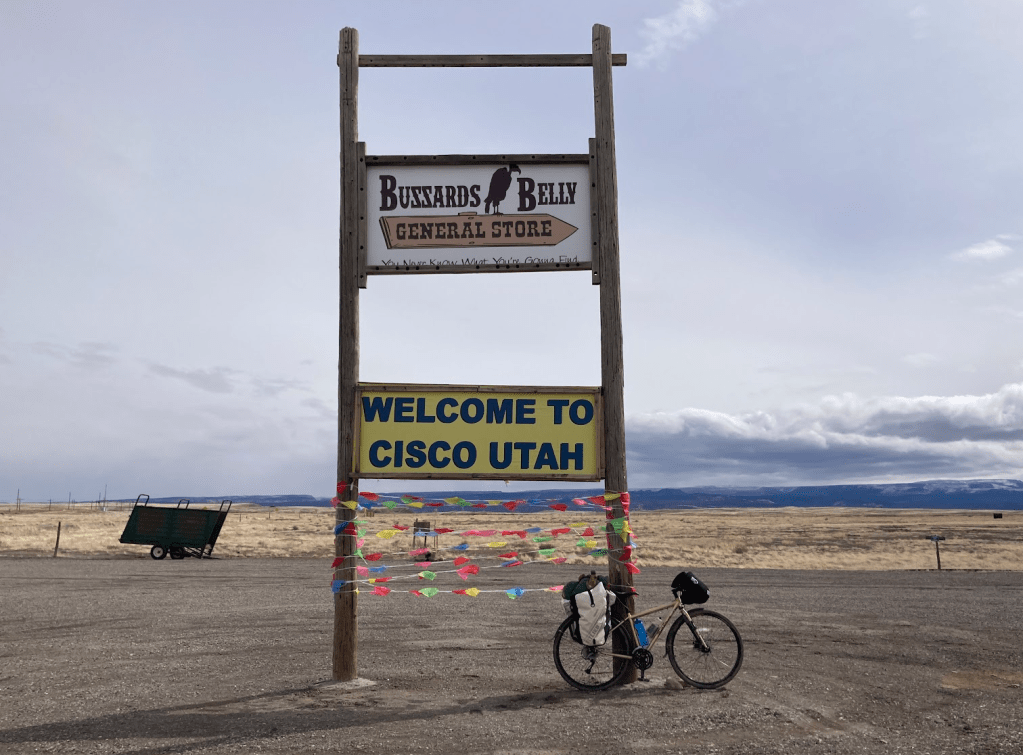

I reached Cisco, a ghost town that marked more than halfway to Moab. I’d been advised not to count on any water being available here, but the singular store appeared to be open today. Buzzards Belly: You Never Know What You’re Gonna Find! I deigned not to find out.

The journey from Grand Junction gave me an abundance of hours to get used to this new biome. I noticed the hills in the desert: not just the ones that I pedaled up and coasted down, but the rest in view as well. They often struck me as somewhat comical in their size and shape, like oversized moguls (from ski slopes), or a hills shaped by a child with play-doh. I felt an urge to lay the bike down and jog up and down some of these lumps in the earth.

Although I rarely spotted any, there were clear signs of cattle history at times, the most obvious being their dung. I also passed two cattle carcasses on the side of the road. They were long dead, mostly empty, bones sticking out. Not having spotted any other carcasses farther away from the road, I assume these had been hit by vehicles. They gave a slightly eerie air to the overcast desert.

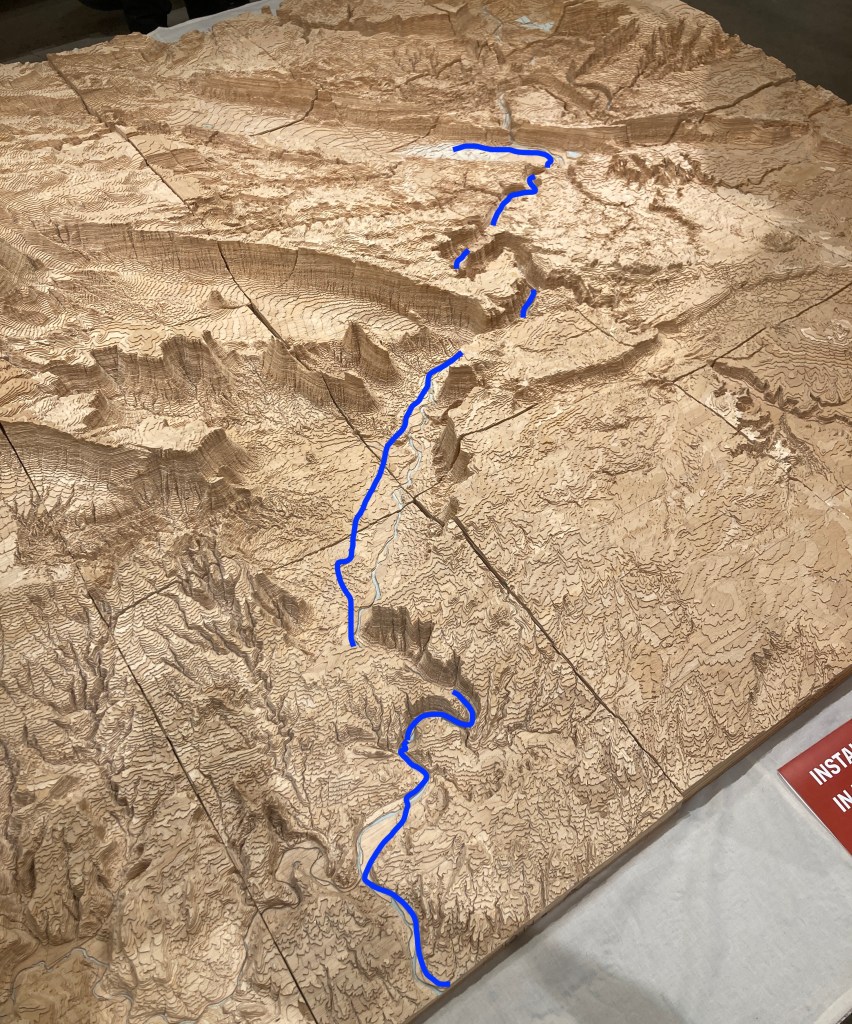

Eventually, as my route cut towards the Colorado River, the relatively flat landscape began to brighten with orangey sandstone formations that grew nearer and taller as I went. I studied the shapes in the distance, trying unsuccessfully decode where amongst them the dozens of miles left would take me. This crescendoed as I approached Moab. Aided by a slight thinning of the clouds, I enjoyed majestic views of towering rock formations that framed the river and sky.

Slowly but surely, the miles ticked off, with the last forty-ish conveniently counted by mile markers. I rolled onto a delightful bike path a few miles out, and by late afternoon, I had arrived in Moab. From there, it was only a handful of miles to the hostel that had been recommended, for a total of about 130 over the two days. I coasted into the gravel parking lot, feeling victorious.

At the front desk, I filled in my guest registration on a scrap of colored paper. It asked for my name, address, and vehicle description. I wrote “none” for the latter.

“No car?”

“Nope.”

“How’d you get here?”

“Bike.”

It’s funny but understandable that that’s surprising in a mountain biking town

Moab is a mountain biking destination. It’s exceedingly common to see cars and campers with one or more mountain bikes hanging off the back. But despite both being fun, gnarly activities on two leg-powered wheels, mountain biking and the kind of bike travel I was doing are very different. Although the experience was full of fun and adventure, I wasn’t biking for recreation alone. I was essentially bike commuting, but far. I was biking to avoid driving. In steep contrast, most mountain bikers drive in order to bike.

They drive the bike to a mountain biking destination, go for a ride, and drive back. The Kokopelli Trail, which has almost the same start and end point as my journey did, takes 3-5 days typically by mountain bike, and has no reliable water sources along it, making it virtually impossible to do with conscripting a vehicle to drop off water caches along the route.

I was thankful that they let me bring my bike up to my (shared) room. To save on loaded bike weight, I had sent my lock ahead of me, along with my tools, in a flat rate box to Moab. I’d pick it up the next day, so I had no lock at the moment.

After a heavenly hot shower (despite the rather painful washing of chafed areas) and starting a badly-needed load of laundry, I sauntered into the hostel kitchen to scope out the free food shelf. I was grateful to find enough ingredients to make a savory dinner of whole wheat rotini with peanut butter, barbecue sauce (stay with me), and canned green beans. In retrospect, I would not normally want to eat that, even with my tolerant palate, but I was very hungry and had eaten only jam sandwiches and caramel flavored nutrition shake for 36 hours, so it was great.

I had made it!!! I had f***ing made it!!! Despite very non-ideal weather and route planning, my plan had basically worked as intended, and I was safety and comfortably in Moab, in time for the internship, which was slated to begin the next day at 1 p.m.

I went to bed and slept well.

Discover more from evoiding

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Excuse my French, but Emily, you are a f***ing boss.

I apologize if that’s offensive. That phrase just kept coming to my mind as I read this post.

LikeLike

Thanks Eugene!

LikeLike

What an adventure! Wow. You’re really, truly LIVING, and I love it! I hope the internship is a fantastic (and enjoyable) learning experience. I’ll be thinking of you!

Casey Renee Rogers

HealthOnTheRocks.com http://healthontherocks.com/ @HealthOnTheRocks https://www.instagram.com/healthontherocks/

LikeLike

Thank you Casey!

LikeLike