I started writing this in February, and just dug it up to finish it before I get into writing my big May travel post. Enjoy!

As the 1-year anniversary of quitting my old battery engineering job rolls by, I’d like to share some reflections about my time at Form Energy.

- How I ended up there

- Working at Form

- Good manager, good life

- The highlights

- What surprised me

- It’s not you, it’s me… Unless?

How I ended up there

Let’s rewind to the spring of 2022. I was about to graduate with a shiny degree in chemical engineering, plus a cheeky computer science minor. I’d done my time as a minion (ahem, undergrad researcher) at a green hydrogen lab, and then smartly taken an electrochemistry course to emphasize my specialty. Then I applied to a whole bunch of energy related jobs.

It worked1: I got five offers in a range of energy-related work. Is it tacky to name them? Eh, whatever.

- Convergent Energy and Power, a renewable energy projects company (NYC)

- BloombergNEF (New Energy Finance), a branch of Bloomberg researching cleantech and finance (NYC)

- BTU Analytics (acquired by FactSet), a power markets data and analytics company (Colorado or something)

- Wood Mackenzie, another power markets data and analytics company (Boston)

- Form Energy, a battery technology startup for utility-scale renewable energy storage. (Boston)

I chose Form for a few reasons:

- I liked the location the best. I was ready for a place more downtempo than NYC, but still wanted to live in a walkable city, with access to cultural events and lots of people. Somerville, MA was perfect.

- I liked the people I’d spoken to, including the person who would be my manager. I came for an on-site tour and the number of flannel shirts I saw was a green flannel flag.

- If I was ever to work a real chemical engineering job, I’d better do it while the degree was fresh.

- Didn’t hurt that it paid the most.

I graduated, and after a few weeks of vacation, I moved to Somerville and started my first grown-up job: a newly minted Battery Engineer I at Form Energy.

Working at Form

I ended up working there for 1 year and 9 months, in the middle of which I promoted to Engineer II. I don’t hesitate one bit to say that it was a good experience. My coworkers were great, the work was engaging. Thanks to being a startup, there were a lot of young folks in their twenties, and lots of women, and I didn’t feel any discrimination or isolation. I was quite shy about making friends at work, finding it very hard to mix being professional with being social (I’ve improved since), so I have some regrets about not better befriending more coworkers.

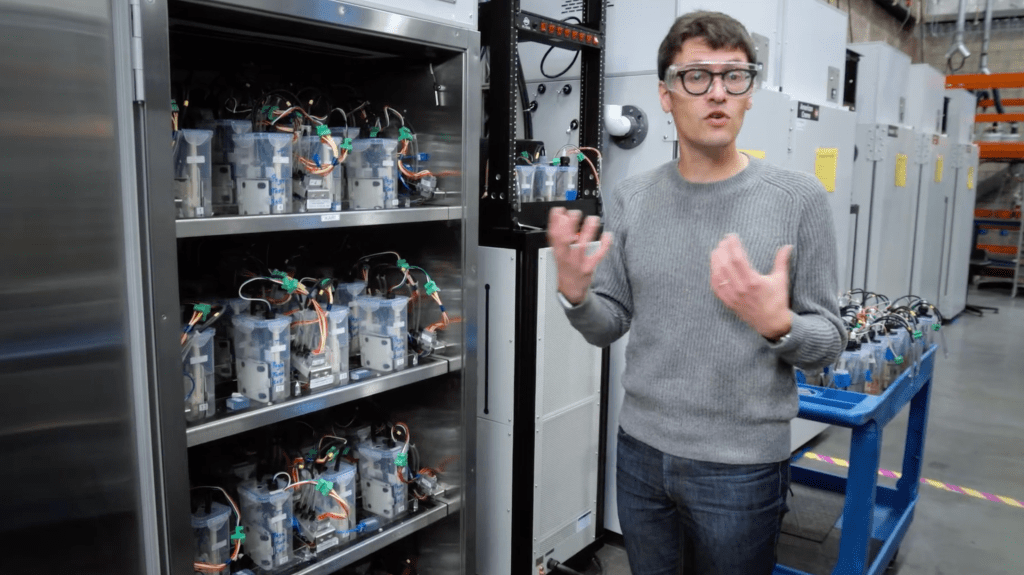

So what was my job, exactly? Basically, I did experiments on small-scale models of our battery and helped analyze our huge body of experimental data. The technology was (and is) being developed, so we had a lot of knobs to turn to try to optimize its performance. Beyond just turning knobs, we wanted to figure out why they had the effects they did, so we could make improvements faster and cheaper. It was a bit like academic research, but faster paced and more exciting.

Images from this promotional video they filmed while I was working there. I worked mainly with those little wired up lunchboxes, called sub-scale cells.

I spent about half my time behind the computer or in meetings, and the other half down in the lab doing checks and fiddling with things that the lab technicians and engineers knew how to do better. By the time I left, my scope had shifted to be almost entirely desk bound.

Good manager, good life

The most important factor in my experience was my manager. I truly don’t think I could have asked for a better manager. He supported me, helped me grow, and celebrated my successes. He also modeled so many good qualities as a manager and teammate. He worked long hours but never pressured others to over-work. In difficult situations, he would almost magically smooth things over. He always brought a positive attitude. He sought feedback and was open about how he was trying to improve. These are qualities I’ve tried to learn from and take with me forward, because they apply anywhere.

What I’ll remember most is his ability to make me feel cared about, both as a human being and as a developing engineer. I learned to always have answers ready for the questions of “What questions do you have?” and “How can I help?”

So, thanks Nick! You raise the bar.

The highlights

One of my favorite parts was data analysis and visualization. It’s something I’ve always found fun. I got pretty good at plotting with JMP, learned a bit more Python, picked up some basic SQL, and developed various personal tastes about graphs.2 I liked being “in the zone” of data analysis, chasing down some hunch or laying out an argument on slides. I got a lot of positive feedback for my ability to clearly present information.

Another favorite thing to do at work was add hyper-specific custom emojis to our Slack. We had a culture of proliferating company memes and inside jokes via Slackmojis. I loved creating tiny graphics that captured a specific feeling about a specific situation, uploading them as Slackmojis, reacting with them to messages, and seeing people notice, laugh, and pile on. Oh yeah. Feels good.

I also quickly became a big contributor to our meme channel on Slack. Once again: hyper-specific feelings about situations, expressed humorously in a medium more powerful (and less explicit) than words. Maybe two months in, I got a shoutout in the the monthly company-wide meeting for my meme-making.

I did abscond with a collection of my memes when I left. Here are several which do not contain anything remotely close to a trade secret. They probably aren’t funny at all out of context.

The thing I was most widely known for in college was probably also making memes on our university meme page. One day, I’ll be in a suitably memeable community again.

I didn’t just grow my meme portfolio though. I grew as a person. I learned so much about working in a professional environment, and gained a lot of skills and confidence. It was a great job, hands down, and I’m grateful that I had the opportunity.

What surprised me

I was surprised by how much I had to contribute right off the bat. In retrospect, I was under-confident at first. One of my first ideas for improving our data monitoring (I’m going to have to speak in very vague terms now) was good, but I didn’t push to pursue it, so it largely fell aside. A year or so later, the overarching issue ended up being extremely pressing and affected pretty much everything. Had I believed in my idea more and chased it down from the start, I might have saved Form a fair bit of money and time.

I was also surprised by how essential you could make yourself by just writing a bit of code. I wrote a few chunks of Python that calculated a certain metric and plotted a graph. It was a fairly simple thing – just something that our standard data processing didn’t do. Well, for weeks and weeks, I would get messages asking me to run the thing on XYZ data so the results could be added to executive-facing slides. I didn’t gate keep it, by the way, as I shared the code and worked on building it into the standard stuff.

I wasn’t the best coder (I mean, there was a full SWE team), but I understood the problem from the user-end and knew enough to solve it good enough for now. That bridging function was the key: understanding the problem well enough to imagine an actually good solution, and understanding the solution cogs enough to work up a functional solution (later working with the experts to polish and set it in stone).

In my time at Form, I saw a fair amount of fumbled batons and awkward situations that could be attributed to a lacking of this bridging. This isn’t necessarily a particular fault of Form, but rather a natural result of having complex problems, large teams, and specialization. I really like bridging these gaps, and it’s something I see myself doing in natural building.

From this, I learned that even in a large organization, full of very talented people, there are low-hanging fruit for those with eyes to see and ability to snatch.

Ok, enough of this LinkedIn drivel.

It’s not you, it’s me… Unless?

If there was so much to like, why did I quit?

The short answer is because I developed rather different plans for my life, and there was no time to waste.

From mid 2023 to early 2024, my progress in the figuring-out-what-to-do-with-my-life accelerated a lot. I decided to become a natural builder (I’ll get to the full details of this in a future post… I promise…) I got my ducks in a row. In January 2024, I put in my 4 weeks notice.

The following few weeks were interesting. This was my first time quitting a job. As it happens, I quickly found out how valued I was. I met with people three levels up. I was asked to name my terms for staying. I chatted with my peers, who were very curious about it all. Being about to peace out really does open a new level of frankness in conversations.

In the end, I stuck to my plan. I wrote thank-you cards to the people I’d worked most closely with. On my last day, teammates kindly gathered at lunch with treats for a sendoff party. Then I grabbed the few remaining items at my desk, turned in my laptop and badge, and anticlimactically slipped out the main entrance.

No more 9-to-5. No more biweekly paycheck. No more team huddles, no more Form memes, no more free lunches. A couple weeks of down time, and then I’d be hopping on the longest train ride of my life, desert-bound. Beyond stretched the blank expanse of life, upon which I’d started sketching.

I biked downtown for an errand. On the way, I stopped on Longfellow Bridge and asked a stranger to snap a picture of me with the sunset. “I just quit my job,” I informed him, and grinned for the camera.

Chronologically, the next posts in this journey are:

Boston to Utah by Train and Bike

My Time in Moab with Community Rebuilds

- So much that I wrote a career advice post, ha ↩︎

- Spider charts are overrated, stacked bar charts are underrated, regressions are highly suspect at all times. ↩︎

Discover more from evoiding

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.